How should the federal government define success for agency websites and applications? How can we, as agile software delivery team members, ensure each system achieves these goals? While every program has different needs, one universal challenge stands out – how to make sure that every user can get the information they need, quickly. Given a user base comprising the American public at large – a varied audience that includes the young, the old, and those with disabilities – how can we help each federal agency fulfill this promise to the people they serve?

A brief history of plain language

In the winter of 1963, a Stanford and Harvard Law graduate named David Mellinkoff first shared his comedic insights into the overly complicated, overly verbose language of legal treatises in The Language of the Law. Federal employees began to take notice, and by the 1970s, Presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter signed orders requiring that certain official U.S. government documents be “written in plain English and understandable to those who must comply with them.” Next, the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980 was passed in response to the public outrage over the ever-increasing number of complicated government forms. The movement continued to coalesce, culminating in the founding of the Plain Language Association International (PLAIN) to bring together experts and provide guidance to many organizations across the globe that were beginning to consider the needs and wants of their users.

These are the true underpinnings of User-Centered or Human-Centered Design, which has become critical to the success of any federal government web project.

Plain language isn’t just a good idea, it’s the law

Since the passage of the Plain Writing Act of 2010, all federal executive agencies are required to put new and revised documents into plain language. The Act defines plain language as “writing that is clear, concise, well-organized, and follows other best practices appropriate to the subject or field and intended audience.” One of the Act’s co-sponsors remarked: “the writing of documents in the standard vernacular English language will bolster and increase the accountability of government within America and will continue to more effectively save time and money in this country.”

Build a content strategy that uses plain language

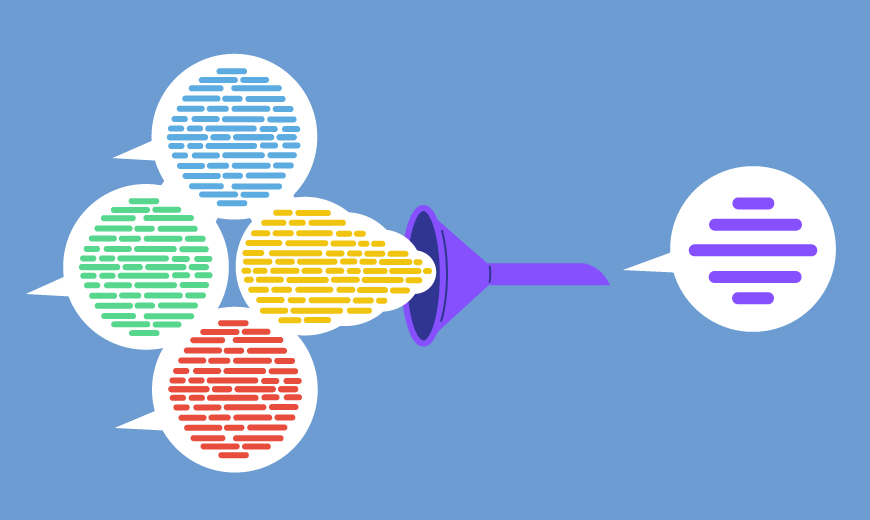

PLAIN encourages agencies to present information that users can: Find – Understand – Use. Whether the resource is a printed form, static website, or interactive application, users need to be able to Find what they need, Understand what they find, and be empowered to Use what they find to meet their needs. In order to provide services to users that meet these three goals, product owners must develop a well-conceived Content Strategy. This integrated set of user-centered, goal-driven choices forms a powerful project foundation. Strong writing, using plain language, is one of the components of a robust content strategy which also may include such elements as photography, videography, and social media. Furthermore, with the limited amount of space on hand-held devices and the flexibility required by usability standards, much copywriting today is actually micro-copywriting. Brief copy elements, such as instructions, button labels, and tool tips, must be short, easy to read, and engaging. We must focus on the language that will project maximum utility to each user in the fewest words.

5 steps to success

At the 2020 Summit, veteran content strategist and plain language advocate Janice Redish suggested there are five steps to developing a content strategy: Discover, Plan, Align, Use, and Govern.

-

In the Discovery phase, project owners articulate the vision, mission, and goals for the project. They also develop the personas for representative users. Ultimately, the problem to be solved is made clear.

-

The project owner next develops a Plan to solve the problem. This plan includes a Style Guide where the plain language guidelines are documented. These guidelines should include the voice and tone of the project and any specific guidance on word choice and phraseology that may be necessary. The Style Guide serves as a single source of truth that designers and developers refer to as they develop the app or website.

-

During the Align phase, stakeholders re-examine the Plan to make sure it fits with what was found during the Discovery phase as well as larger strategies in the organization. Additionally, the Plan is used to inventory any existing content, to audit that content, and to develop the content.

-

Finally, a content strategy includes instructions to Govern future development and management of the content after the initial project has been deployed.

Having a Content Strategy at the outset of a project ensures consistency and increases your odds of success. Of course, your chosen tactics are what breathe life into the plan. They will sustain (or eventually destroy) the project. For example, comprehensive inventory of current content is a critical tactic in the Discovery phase. This might include such details as URLs that link to a page and the date the page was created. Also, an audit of this inventory will surface elements that are working or not working in the project. Regular usability testing of the content, including language used, will guide the team to what improvements could and should be made. These are just a few of the many tactics that can be used to support a successful Content Strategy.

Through a cycle of regular feedback, thoughtful and flexible content strategy execution, and the use of plain language, users will more readily take advantage of the services you provide. Whether upgrading the language to be more conversational or using more familiar, common words to express the message, the end result will be a product that is more usable – and consequently more useful. By using plain language, we are not dumbing down the content to cater to the reader with the least understanding. Rather, using language that communicates information quickly and clearly benefits everyone.

In the end, technology can only further agency goals to the extent that content can be found, understood, and acted upon by each user. Make every word count.